Summary

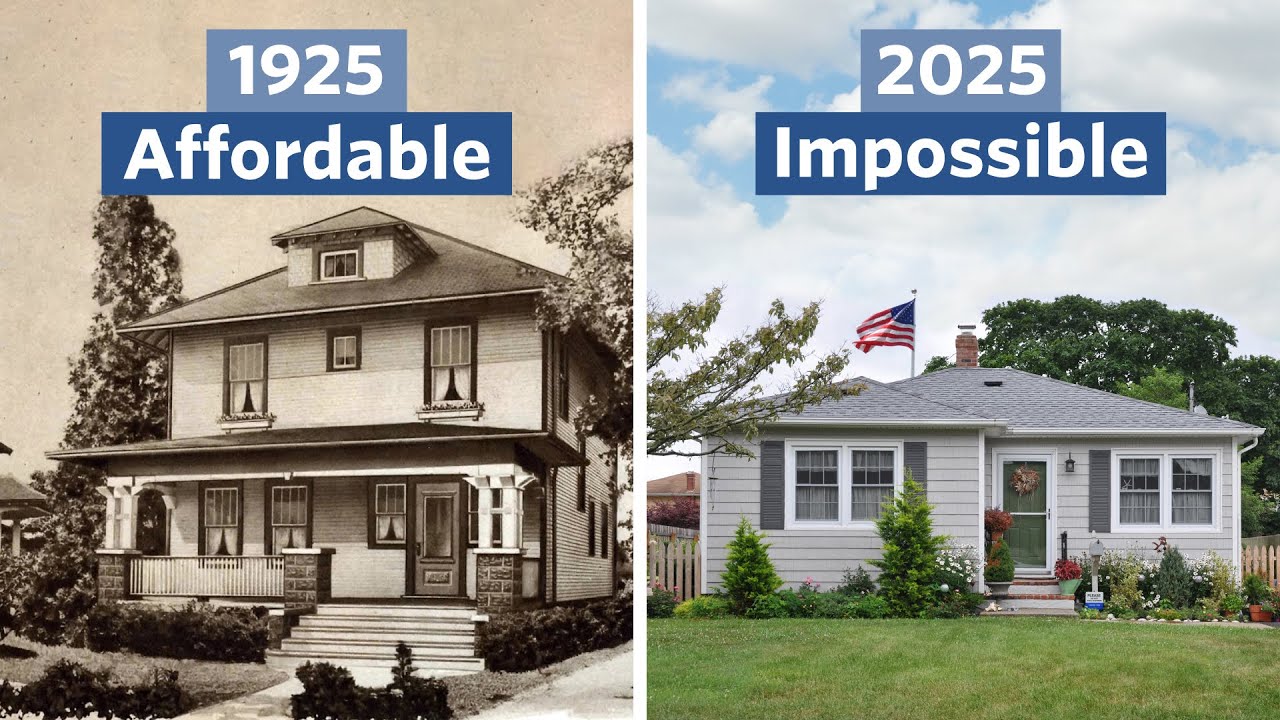

The video provides a comprehensive historical perspective on the U.S. housing affordability crisis, tracing its roots back over a century to understand how supply, financing, and policy have shaped the current landscape. It begins by examining the housing boom of the 1920s, fueled by the rise of automobiles, lax regulations, and expanding credit, which allowed widespread suburban development. The introduction of zoning laws in the 1920s established regulatory frameworks that would later restrict housing supply. The Great Depression and World War II halted private sector housing construction, prompting the federal government to intervene with loan guarantees and public housing programs—though these efforts had mixed outcomes, often focusing on slum clearance rather than increasing affordable housing stock.

Post-World War II, returning veterans faced severe housing shortages, leading to mass production of affordable suburban homes like Levittowns. The expansion of 30-year mortgages and low interest rates made homeownership widely attainable, increasing ownership rates dramatically. However, public housing policies continued to emphasize urban renewal and slum clearance, often displacing low-income residents and concentrating poverty.

The 1970s marked a turning point with the rise of exclusionary zoning and ‘NIMBYism’ (Not In My Backyard activism), which restricted multifamily and affordable housing development, often reinforcing racial and economic segregation despite the Fair Housing Act of 1968. During this period, housing began to be increasingly financialized—viewed as an investment vehicle rather than merely a home—attracting corporate investors and real estate investment trusts (REITs) that bought and sold residential properties on a large scale.

The modern era was defined by the 2008 subprime mortgage crisis, a direct consequence of financialization, which triggered a housing market collapse and stalled construction. Meanwhile, household formation increased due to population growth and shrinking household sizes, exacerbating the shortage of affordable homes. Rising rents and home prices outpaced wages, increasing cost burdens on renters and buyers alike. Institutional investors have been blamed for increasing rents by purchasing single-family homes to rent at higher prices, although they represent a small portion of the market.

Modern NIMBYism continues to impede housing supply by opposing new development projects, citing concerns about traffic, noise, and property values. Unlike earlier suburban expansions, today’s urban infill projects face significant local opposition, complicating efforts to address housing shortages.

Looking forward, the video suggests cautious optimism: builders are exploring “missing middle” housing that fits smaller lots and urban infill needs; progressive policies are emerging to ease restrictions on accessory dwelling units and other housing types; however, financing conditions are unlikely to become more favorable, and the financialization trend is expected to continue. Public housing construction remains unlikely to expand significantly without strong federal support. The video closes by promoting Eastern Washington University’s urban planning programs as a way to equip new professionals to tackle these housing challenges, highlighting Spokane’s progressive zoning reforms as a real-world example of innovative urban planning.

Originally posted 2025-08-25 01:34:00.